Helen, Queen of the Nautch Girls

Quartet

t has been said that most great twentieth century novels include scenes in a hotel, a symptom of the vast uprooting that has occurred in the last century: James Ivory begins Quartet with a montage of the hotels of Montparnasse, a quiet prelude before our introduction to the violently lost souls who inhabit them.

Adapted from the 1928 autobiographical novel by Jean Rhys, Quartet is the story of a love quadrangle between a complicated young West Indian woman named Marya (played by Isabelle Adjani), her husband Stefan (Anthony Higgins), a manipulative English art patron named Heidler (Alan Bates), and his painter wife Lois (Maggie Smith). The film is set in the Golden Age of Paris, Hemingway's "moveable feast" of cafe culture and extravagant nightlife, glitter and literati: yet underneath is the outline of something sinister beneath the polished brasses and brasseries.

When Marya's husband is put in a Paris prison on charges of selling stolen art works, she is left indigent and is taken in by Heidler and his wife: the predatory Englishman (whose character Rhys bases on the novelist Ford Madox Ford) is quick to take advantage of the new living arrangement, and Marya finds herself in a stranglehold between husband and wife. Lovers alternately gravitate toward and are repelled by each other, now professing their love, now confessing their brutal indifference -- all the while keeping up appearances. The film explores the vast territory between the "nice" and the "good," between outward refinement and inner darkness: after one violent episode, Lois asks Marya not to speak of it to the Paris crowd. "Is that all you're worried about?" demands an outraged Marya. "Yes," Lois replies with icy candor, "as a matter of fact."

Adjani won the Best Actress award at Cannes for her performances in Quartet: her Marya is a volatile compound of French schoolgirl and scorned mistress, veering between tremulous joy and hysterical outburst. Smith shines in one of her most memorable roles: she imbues Lois with a Katherine-of-Aragon impotent rage, as humiliated as she is powerless in the face of her husband's choices. Her interactions with Bates are scenes from a marriage that has moved from disillusionment to pale acceptance.

Ruth Prawer Jhabvala and James Ivory's screenplay uses Rhys's novel as a foundation from which it constructs a world that is both true to the novel and distinctive in its own right, painting a society that has lost its inhibitions and inadvertently lost its soul. We are taken to mirrored cafes, then move through the looking glass: Marya, in one scene, is offered a job as a model and then finds herself in a sadomasochistic pornographer's studio. The film, as photographed by Pierre Lhomme, creates thoroughly cinematic moments that Rhy's novel could not have attempted: in one of the Ivory's most memorable scenes, a black American chanteuse (extraordinarily played by Armelia McQueen) entertains Parisian patrons with a big and brassy jazz song, neither subtle nor elegant. Ivory keeps the camera on the singer's act: there is something in her unguarded smile that makes the danger beneath Montparnasse manners seem more acute.

News

Heat and Dust

Adapted by Ruth Prawer Jhabvala from her Booker Prize-winning novel , Heat and Dust is the story of two English women living in India more than fifty years apart. Olivia (Greta Scacchi) shares a troubled marriage with Douglas Rivers (Christopher Cazenove), an English civil servant in the colonial India of the 1920s. Anne, Olivia's grand niece (Julie Christie), comes to the subcontinent -- thirty years after the sun has set on the British empire -- to investigate Olivia's life, which her family regarded as "something dark and terrible."

Shortly after her passage to India in 1923, the beautiful young Olivia finds herself bored by English colonial social circles -- she wonders how people who lead such exciting lives could remain so dull --though she is entranced by India itself. Olivia is introduced to the Nawab of Khatm (Shashi Kapoor), a romantic and decadent minor prince who enjoys a Forsterian intimacy with his British confidant, Harry (Nickolas Grace). The willful Englishwoman begins going to Khatm to spend time with the Nawab and they fall in love, engaging in an affair that is not without wrenching consequences in her public and private lives.

In the present day of the film, Anne investigates Olivia's past with Inder Lal (Zakir Hussain), her Indian landlord. Anne finds herself both in the same rooms and in the same predicament as her ancestress, as she herself becomes involved in a romantic entangelment with an Indian man. Heat and Dust cross-cuts between the lives of the two women as Anne discovers -- and then seems to repeat -- the scandal that her independent-minded ancestor caused two generations before. Anne must then re-assert her own independence, fifty years later.

The supporting cast of the film includes Madhur Jaffrey as the Begum, the Nawab's manipulative mother who holds court like a lioness among the purdah ladies; Charles McCaughan as Chid, the American sanyasi and would-be holy man; Patrick Godfrey as Dr. Saunders, in the first of his many turns as an uncompromising Englishman for Merchant Ivory; and Jennifer Kendal as his childless and mirthless wife.

Jhabvala writes in her novel that, to Olivia, being in India "was like being not in a different part of this world but in another world altogether, in another reality." Scacchi's radiant performance never ceases to convey her wonder at the brave new world she finds in the colonial subcontinent, even late in the film when that view is tempered by the reality of an impossible dilemma. Her on-screen chemistry with Shashi Kapoor, who gives a textured portrayal of a outlaw prince, is apparent from their first moment of eye contact . In the present day of the film, Christie brings a warmth and intelligence to Anne that is at once sensuous and true to the thoughtful voice of Jhabvala's novel.

The India of Heat and Dust is a balance of visual splendor and the understated ironies that are characteristic of Ivory-Jhabvala work. Merchant spares nothing in the production values -- we move from ornate banquets in 1923 to breathtaking vistas in present-day Kashmir -- yet the film's grand exteriors provide the backdrop to closely observed interior lives. The director views India with a lens that is equally informed by his lyrical early work on the subcontinent (The Householder, Shakespeare Wallah), and by his later penetrating social scenes of Henry James and Jean Rhys (The Europeans, Quartet). Richard Robbins provides the music and the score is among his best, employing Indian master musicians in arrangements that bridge Indian classical with 1920s period songs.

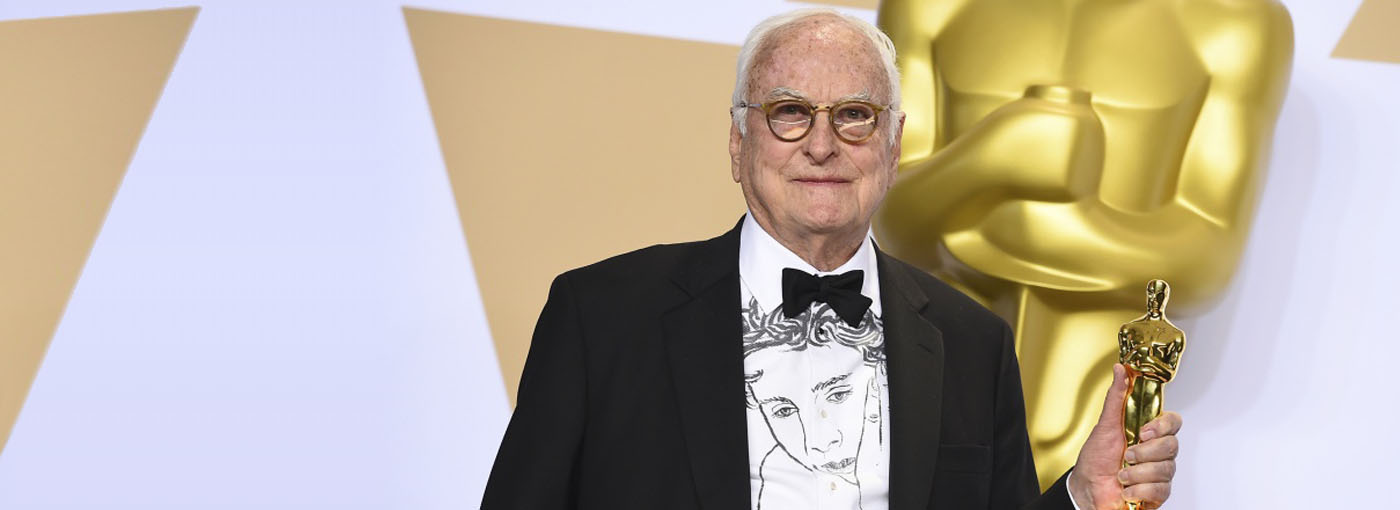

James Ivory Takes Home the Oscar for Best Adapted Screenplay

Social

Subscribe now and stay up to date

Stay up to date on new releases and re-releases of your favorites