Even before Picasso's death in 1973, some of those who knew him, including at least two of the women who shared his life, had published their personal accounts of what it was like to be intimate with the greatest artistic genius of the twentieth century. The most striking of these was Francoise Gilot's Life with Picasso, which appeared in 1964 despite Picasso's strenuous efforts to block its publication on the grounds that it was an intolerable intrusion on his privacy. Gilot depicts Picasso as a man with an imperial ego who often made the women in his life his victims or martyrs. "Pablo's many stories and reminiscences about Olga and Marie-Thérèse and Dora Maar," she writes, "as well as their continuous presence just offstage in our own life together, gradually made me realize that he had a kind of Bluebeard complex that made him want to cut off the heads of all the women he had collected in his little private museum." The comparison to Bluebeard may go too far, but there is no denying the high casualty rate among the women whom stood too near Picasso. His first wife, Olga Koklova, went insane; Marie-Thérèse Walter hanged herself; Dora Maar sank into temporary madness; and Jacqueline Roque, Picasso's wife in the final part of his life, shot herself. Gilot, after a ten-year relationship (from 1943 to 1953) and two children by him, was the only woman with enough strength of will to leave Picasso.

Thus the title of the film, and its plot-line: world-famous artist (in his sixties) meets independent young artist (in her twenties), and charms her into becoming his partner, muse, and mother of his children. When his feelings for her cool, and he turns mean, she walks out, not wanting to become a dreary victim, like her predecessors.

Just as Picasso went to court (unsuccessfully) to stop Gilot's book, so his heirs tried to stop the making of this film. They, too, failed, but the viewer should not expect to see any of Picasso's masterpieces: in a gesture more and more common these days as filmmakers announce their plans to make films about modern artists, Picasso's estate banned any reproduction of his art in Surviving Picasso.

Director’s Comments

Why the Picasso heirs were so against the making of Surviving Picasso was never explained to us. Francoise Gilot, to whom we sent the script, objected through her lawyer that the film would be an invasion of privacy, just as Picasso had done when she attempted to publish her book Life With Picasso in 1964.

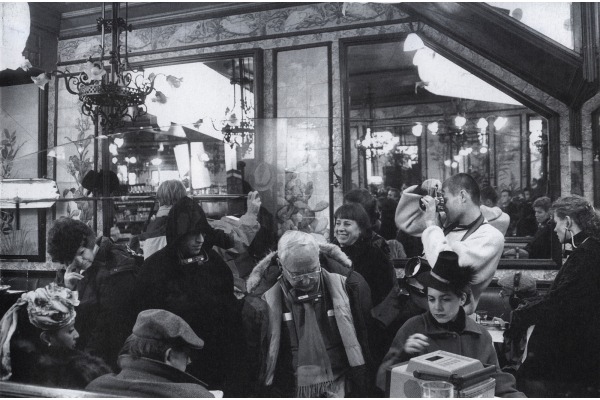

Gilot's son, Claude Picasso, tensely met with us once before mounting a campaign to stop the film. This included telephone calls to Warner Brothers in Los Angeles who, after several years of development, had a considerable investment in the project. Failing there, Picasso then forbade us the use of his father's work. This was a blow, but not a mortal one: whether we showed Picasso's art or not, the story of his relationship with Francoise Gilot stayed the same. We had of course set out to make a better film, one enhanced by Picasso's inventions, from Guernica to ceramic plates to doodles on restaurant tablecloths. Sometimes it was necessary for us to show the master at work and we resorted to half-finished look a-likes. These fakes weren't that bad, I thought.

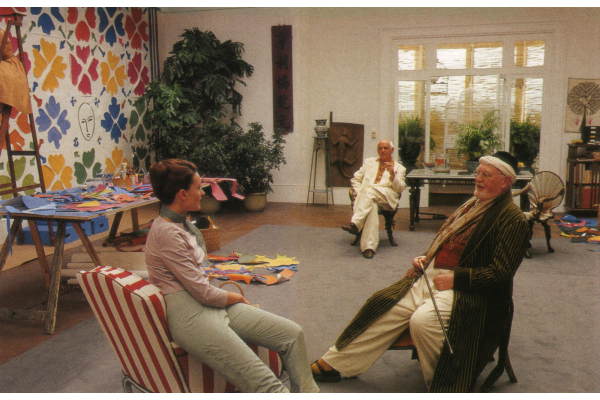

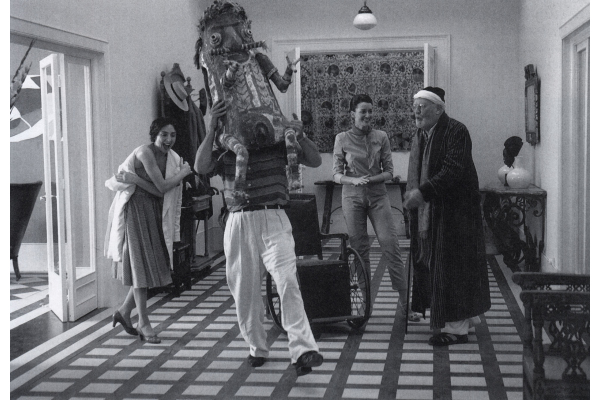

More than any other thing we did or did not do, the use of Picasso look-alikes infuriated the artist's estate, and its spokesmen, as well as some reviewers. Logically, the Succession Picasso, as it is grandly styled, could not refuse us the rights to the artist's work and then complain that the art created for the film as a result of that decision wasn�t up to Picasso's standard. But that is what happened. One English journalist actually wrote that the film thereby put "the artist and his work at considerable risk by playing into the hands of modern-art haters." (This, in 1996!) If so, there is no one to blame but the artist's heirs, who also denied the film's audiences the pleasure they rightfully expected of seeing the Master's art on-screen. Fortunately, audiences were able to feast their eyes on the art of Matisse in two of the film's main sequences: one set in the stained-glass interior of his chapel at Vence; the other set in a re-creation of the artist's nearby Riviera studio, where a group of magnificent collages, paintings, and drawings had been assembled. It boils down to this: a businessman stepped in and tried to stop one artist from making a film about another artist. In the end, the reputation of neither artist suffered much from the film. It was the fun of the audience that suffered -and my fun, of course.

When the film came out, Claude Picasso denounced it in the French press without having seen it. It was enough, he told the Journal de Dimanche, that his friends had viewed it and pronounced their verdict. Their verdict, he said, was "sans appel" -without appeal. But surely by that time the heirs to the Succession Picassomust have realized it had been shortsighted of them to ban the use of real Picassos in a film that was going to be made no matter what, and which has now gone out and been marketed all over the world, in ever-expanding forms of media, with substitute art that displeases them.