Helen, Queen of the Nautch Girls

Howards End

Based on the 1910 novel, Howards End is a tour-de-force portrayal of E.M. Forster's masterpiece about a society in transition. The film was named Best Picture of 1992 by the National Board of Review, received nine Academy Award nominations, including that of Best Picture, and was one of the most critically acclaimed pictures of the 90s.

The free-spirited, free-thinking Schlegel sisters, Margaret (played by Emma Thompson, who received an Academy Award for her performance) and Helen (played by Helena Bonham Carter), are swept into a relationship with the Wilcoxes, a wealthy conservative English trading family; and the Basts, a couple near the lowest tier of the Edwardian class system. In an ever deepening palimpsest of relationships and obligations, Margaret must reconcile her irrepressible, independent spirit with her desire for companionship, and Helen must come to terms with her sister's choices and her unexpected passion for a match that, seemingly, should never be.

In a luminous, Oscar-nominated performance, Vanessa Redgrave is Mrs. Wilcox, a matriarch holding fast to a vanishing, remembered England of her childhood at the country house, Howards End. Her husband, Henry Wilcox (played by Anthony Hopkins), is an unyielding traditionalist who must face his own past and the changing world around him. Samuel West brings an assured sensitivity to Leonard Bast, whose aspirations above his class are inspired, and ultimately, rebuked.

Shot on location in England -- from the Hertfordshire countryside to the tenements of London's East End - Howards End won an Art Direction Academy Award for Luciana Arrighi's re-creation of the world known to Forster and his contemporaries. Ruth Prawer Jhabvala received her second Academy Award for her screenplay adaptation, which captures both the quick wit of Bloomsbury parlors and the quiet interiority of Forster's novel.

Ivory's unforgettable translation of Forster's themes into striking images (Mrs. Wilcox's lyrical walk around the house of her childhood; Leonard Bast's sun-drenched fantasies at his insurance clerk's desk), and the performances of an impeccable English cast make Howards End one of the Merchant Ivory team's most moving and perfectly realized films.

News

The Deceivers

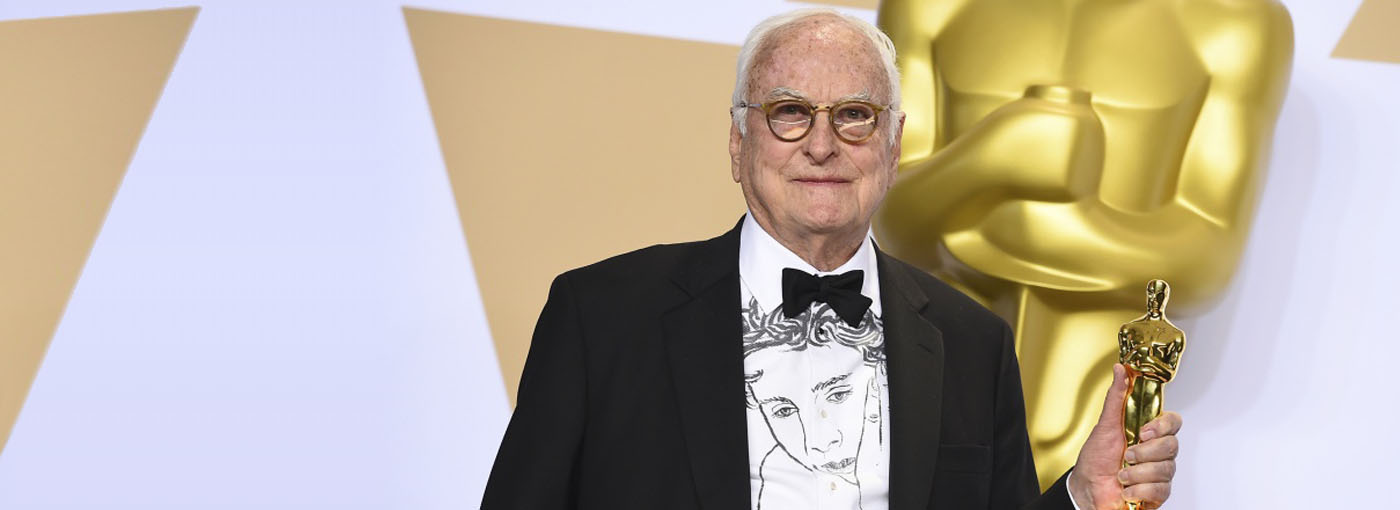

James Ivory Takes Home the Oscar for Best Adapted Screenplay

Social

Subscribe now and stay up to date

Stay up to date on new releases and re-releases of your favorites