Helen, Queen of the Nautch Girls

Quartet

t has been said that most great twentieth century novels include scenes in a hotel, a symptom of the vast uprooting that has occurred in the last century: James Ivory begins Quartet with a montage of the hotels of Montparnasse, a quiet prelude before our introduction to the violently lost souls who inhabit them.

Adapted from the 1928 autobiographical novel by Jean Rhys, Quartet is the story of a love quadrangle between a complicated young West Indian woman named Marya (played by Isabelle Adjani), her husband Stefan (Anthony Higgins), a manipulative English art patron named Heidler (Alan Bates), and his painter wife Lois (Maggie Smith). The film is set in the Golden Age of Paris, Hemingway's "moveable feast" of cafe culture and extravagant nightlife, glitter and literati: yet underneath is the outline of something sinister beneath the polished brasses and brasseries.

When Marya's husband is put in a Paris prison on charges of selling stolen art works, she is left indigent and is taken in by Heidler and his wife: the predatory Englishman (whose character Rhys bases on the novelist Ford Madox Ford) is quick to take advantage of the new living arrangement, and Marya finds herself in a stranglehold between husband and wife. Lovers alternately gravitate toward and are repelled by each other, now professing their love, now confessing their brutal indifference -- all the while keeping up appearances. The film explores the vast territory between the "nice" and the "good," between outward refinement and inner darkness: after one violent episode, Lois asks Marya not to speak of it to the Paris crowd. "Is that all you're worried about?" demands an outraged Marya. "Yes," Lois replies with icy candor, "as a matter of fact."

Adjani won the Best Actress award at Cannes for her performances in Quartet: her Marya is a volatile compound of French schoolgirl and scorned mistress, veering between tremulous joy and hysterical outburst. Smith shines in one of her most memorable roles: she imbues Lois with a Katherine-of-Aragon impotent rage, as humiliated as she is powerless in the face of her husband's choices. Her interactions with Bates are scenes from a marriage that has moved from disillusionment to pale acceptance.

Ruth Prawer Jhabvala and James Ivory's screenplay uses Rhys's novel as a foundation from which it constructs a world that is both true to the novel and distinctive in its own right, painting a society that has lost its inhibitions and inadvertently lost its soul. We are taken to mirrored cafes, then move through the looking glass: Marya, in one scene, is offered a job as a model and then finds herself in a sadomasochistic pornographer's studio. The film, as photographed by Pierre Lhomme, creates thoroughly cinematic moments that Rhy's novel could not have attempted: in one of the Ivory's most memorable scenes, a black American chanteuse (extraordinarily played by Armelia McQueen) entertains Parisian patrons with a big and brassy jazz song, neither subtle nor elegant. Ivory keeps the camera on the singer's act: there is something in her unguarded smile that makes the danger beneath Montparnasse manners seem more acute.

News

The Ballad of the Sad Café

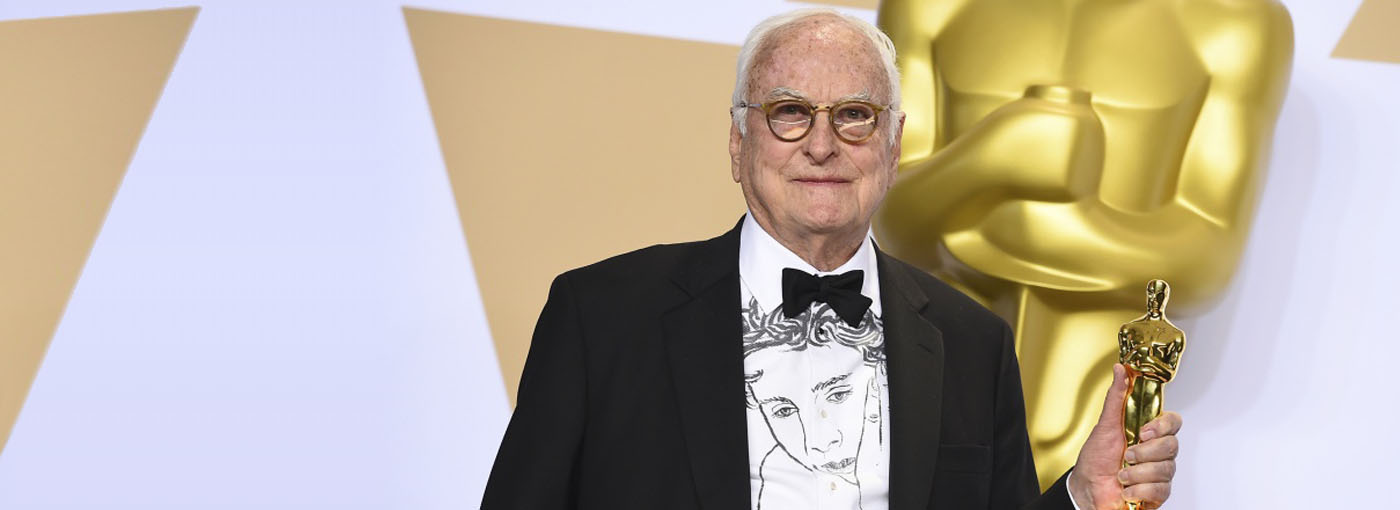

James Ivory Takes Home the Oscar for Best Adapted Screenplay

Social

Subscribe now and stay up to date

Stay up to date on new releases and re-releases of your favorites